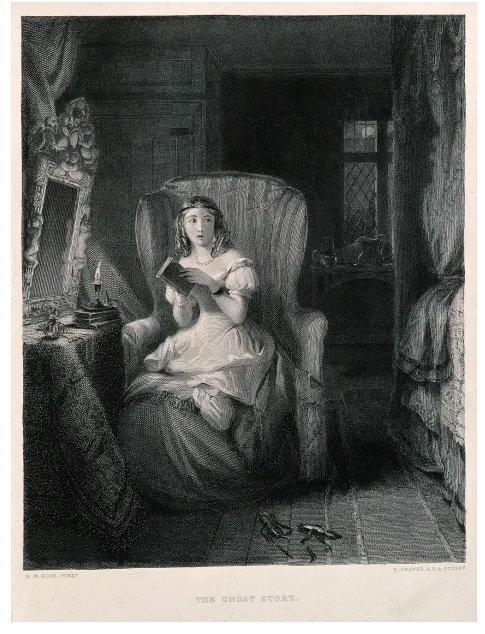

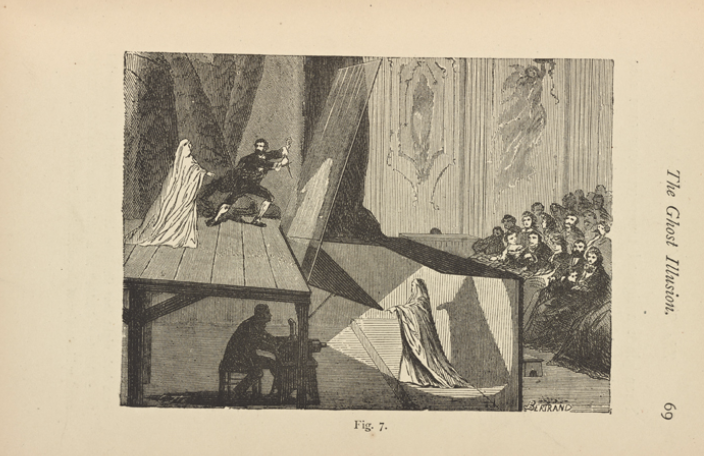

Mid-nineteenth-century English Christmases were saturated with ghost stories.

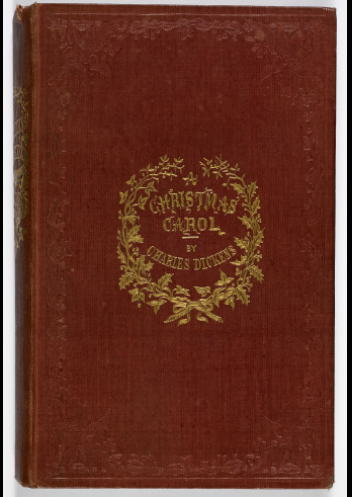

The oral tradition of gathering around the fire to share chilling stories during the longest nights of the year had been parlayed into a successful holiday marketing strategy. One used to push gilded red gift books and special editions of popular magazines.

Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is just one notable example of these ubiquitous Christmastime must-have gifts. It was published on December 17, 1843, and was sold out by Christmas.

As it still does today, such familiarity bred contempt.

To my surprised delight, as I was dipping my toes into the academic study of Victorian Christmas books, I stumbled upon satire of this haunted genre.

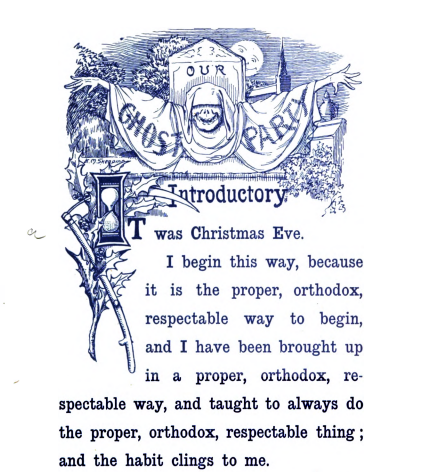

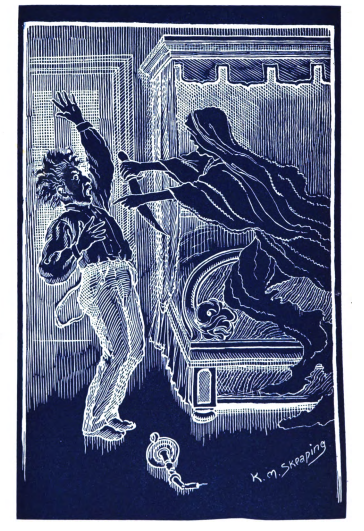

First, I found Tales Told After Supper, written by Jerome K. Jerome and illustrated by Kenneth M. Skeaping in 1891. This is a parody of the standard written Victorian Christmas ghost story device: The framed tale, which uses the main story to set the stage for telling other stories.

Jerome tells us that “Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve they start telling each other ghost stories…. It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood.”

He then allows us to join a group of drunken men sharing copious amounts of whiskey punch and their lampooned ghost stories.

These tales feature various caricatures. One is a weeping ghost that is too depressing to be borne. Another is a foolish gentleman, who, thinking that a spirit leads him to a hidden treasure, nightly dismantles parts of his home until the house is destroyed.

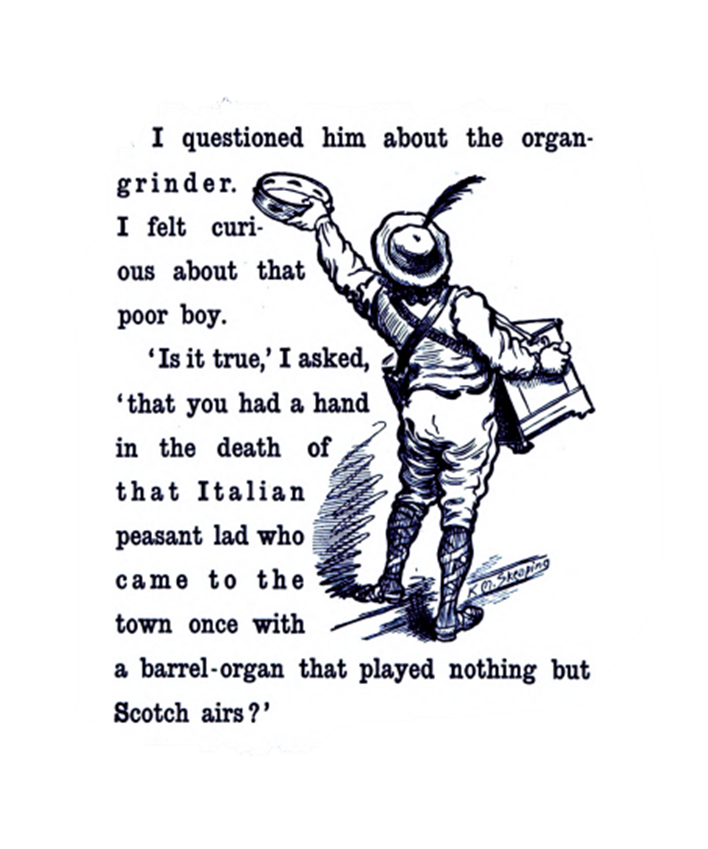

My favorite is the tale of a man who was cursed to become a ghost for murdering all manner of noisy neighborhood people. Among his victims’ number muffin men, carolers, and organ grinders.

The narrator claims of the murderer, “Young men and women who recited long and dreary poems at evening parties, and callow youths who walked about the streets late at night, playing concertinas, he used to get together and poison in batches of ten, so as to save expense; and park orators and temperance lecturers [he] used to shut up six in a small room with a glass of water and a collection-box apiece, and let them talk each other to death.”

This night of tale-telling continues until the celebrants fall asleep at the table, and the narrator goes out in his nightclothes and harasses the neighborhood policeman.

Then I discovered the 1919 essay, “The Passing of the Christmas Ghost Story” in The Bookman: a Review of Books and Life, by Stephen Leacock. This charmer starts by comparing the modern New York Christmas to Victorian country estate Christmases of the past.

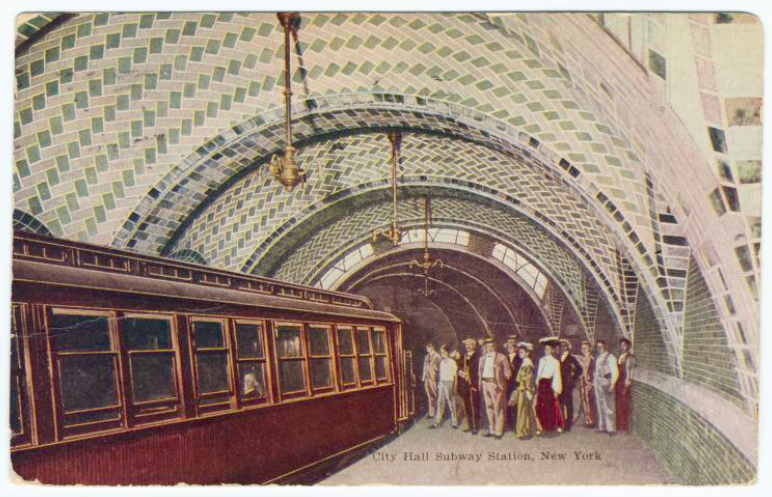

Victorian country Christmases required guests to struggle through a cold and challenging journey to arrive at their destination. Leacock asserts these guests had earned the comfort of the best seats by the fire and to be plied with hot drinks. As opposed to, “Take as against this a Christmas in a New York apartment with the guests arriving by the subway and the elevator, or with no greater highwayman to fear than the taxi cab driver. Warm them up with spiced ale? They’re not worth it.”

Leacock goes on to muse that the modern world has also displaced many of the old Christmas ghost story tropes.

For example, the wind sighing around the chimney, which frightened those living in the mid-19th century, would not have the same impact on those living in the 20th. Since modern guests would arrive in cars instead of horse-drawn carriages, the car’s engines would drown out any wind moaning about the masonry.

Further, if the gathering heard the gusts while inside, they could always phone a tradesman, “Hullo this is Buggam Grange speaking. The wind is soughing rather badly round one of our chimney tops. Will you please send up a man?”

He goes on to poke at additional worn-out ghost story conventions. Such as one can expect the ghost has been murdered precisely fifty years ago and never forty-nine. Or that the butler of the manor has just one trick to add to the atmosphere, “another melancholy shake of his head.” And that, “No man I think can be blamed for admitting he lives in deadly fear of miscellaneous phenomena. We all do.”

Finally, we learn that in the bright modern world of 1919, ghosts are just too common and passe to be feared. “So the ghost story is dead. Let it rest in peace — if it can.”

In the twilight of 2021, I like to think that we have had enough space from the Victorian Christmas ghost story to enjoy it anew. And so, I do hope you will enjoy the samples of stories I share in the below links.

Academic M.R. James (1862–1936) savored the tradition of Christmas ghost stories by composing them to read aloud on Christmas Eve to his friends and select students at Cambridge. Learn more about him and access Kindle, Epub, or PDF versions of his ghost stories.

With a 1933 publication date, we see a later than expected Christmas ghost story in “The Crown Darby Plate” by Marjorie Bowen (1885–1952). This English writer would have grown up with Christmas ghost stories and applied this immersion to her writing. How could you possibly resist an opening line like this: “Martha Pym said that she had never seen a ghost and that she would very much like to do so, ‘particularly at Christmas, for you can laugh as you like, that is the correct time to see a ghost.’ ”

I also urge you to read Tales Told After Supper by Jerome K. Jerome. It is hilarious, and the language feels surprisingly contemporary for something written 130 years ago.

References

Jerome, J. K. (1891). Told after supper, by Jerome K. Jerome ... with 96 or 97 illustrations by Kenneth M. Skeaping. Leadenhall Press.

Leacock, S. (1919). The Passing of the Christmas Ghost Story. The Bookman; a Review of Books and Life (1895-1933), 50, 257.

Moore, T. (2006). Victorian christmas books: A seasonal reading phenomenon (Order No. 3221087) [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Delaware]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

University of Glasgow (1999, December). Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol. Charles Dickens: A Christmas Carol (gla.ac.uk)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting me a buck a month on Patreon by clicking on the link below.

This post was made possible with the generous support of the following patrons. Thank You!

- Kid Cryptid

- Pat Schoettker