The implicit ideas and values that weave through our writing are called themes. These are what our stories are really about just below the surface.

For example, J.R.R. Tolkien may have plotted Bilbo all the way to the Misty Mountains and back again to the Shire, but underneath the adventure was an exploration of the comparative values of material wealth and conflict versus simple pleasures and peace.

Themes

There are many different literary themes. Here are a few of my favorites:

Creators of stories, song lyrics, poems, movie scripts, and plays take advantage of themes such as these to make meaning and allow the audience to connect emotionally to their work.

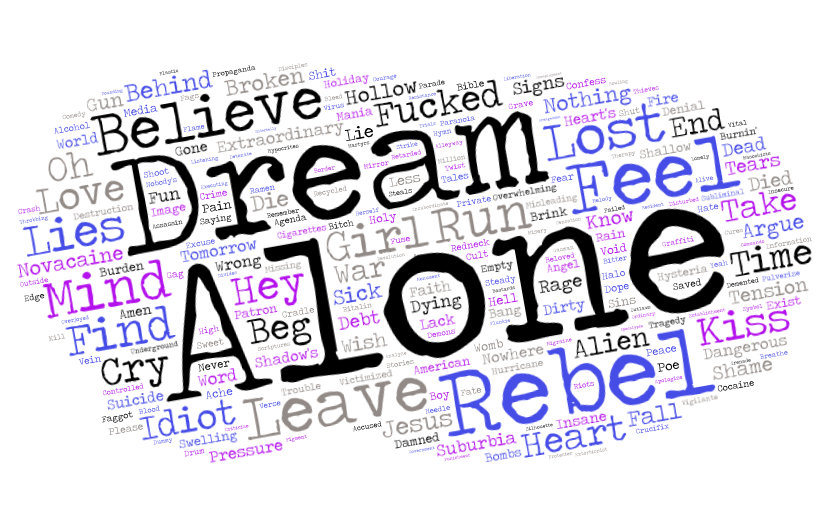

Just for fun, I ran the lyrics of my favorite songs from Green Day’s American Idiot album (i.e., most of them) through a word cloud generator. The more common words appear in a larger font. The results did not surprise me as the major themes that emerged captured the elements of the songs that most resonate with me.

Finding Your Theme

Just like with all things writing, there is no one set path for finding theme clarity.

Some people like to pick out their themes ahead of time, and some prefer to see what emerges as they write their story and then refine them in later drafts.

I am a mixed-methods woman myself when it comes to writing. I like to free-form a rough start of the story first. This helps me develop my characters and world-build. It also gives me a sneak peek of the themes hidden in the story.

After that initial way finding draft, I switch gears and outline the story from soup to nuts, which I find further clarifies the themes. Then, I deliberately tweak the outline to support the development of the themes before I begin focused writing.

Laying the Breadcrumbs

Themes should not be morality hammers. If your readers feel like you are preaching to them, they will disengage. Instead, leave clues so your readers can figure out the themes themselves (or not).

Your story at its heart is an exploration of a theme, from inciting incident to resolution. There are many opportunities to present traces of your theme to your reader:

- Premise

- Characters’ flaws or strengths

- Setting

- Dialogue

- Characters’ growth or downfall

- Key plot points

- Obstacles

- Conflicts

- Repeating ideas

- Symbols/Motifs

Less is More

You can have more than one theme in a story, but having too many makes it difficult to tease out the signal from the noise. Keep things simple so your most important theme clearly rings out. Having a deep connection to a theme is one reason a reader can’t set that perfect book down. Make sure your critical theme can be perceived!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting me a buck a month on Patreon by clicking on the link below.

Become a Patron!This post was made possible with the generous support of the following patrons. Thank You!

- Kid Cryptid

- Cynthia Keller

- Pat Schoettker